By Josephine Chow

Chinese companies looking for deals abroad face five main challenges when globalizing through M&A —including the often overlooked human capital.

Recently, Germany, Japan and the United States have seen a spate of inbound M&A transactions initiated by Chinese manufacturers. The reason is clear: the Chinese manufacturing industry is in desperate need of advancement. This phenomenon tells us a few things: that global industrial transformation has reached its peak; many industries are still hard-pressed for capital as a long-term consequence of the 2008 financial crisis; and the value of the renminbi has empowered Chinese enterprises to expand.

Challenge 1: Underestimating the importance of HR due diligence and the human aspect of a deal

In the majority of cases, M&A is based on human interactions. HR functions should be involved early to avoid disruptions and ensure a smooth transition. The importance of HR is often underestimated by Asian organizations, and Chinese companies are no different. Assessing possible human risk is often thought of as “soft,” but a failure to do so could result in significant “hard” financial losses.

When a Chinese electronics company acquired a French electronics firm, leadership planned to selectively retain employees according to their M&A goals. However, in France, the law protects the disadvantaged so companies cannot easily lay off old, sick, or disabled employees. The company would have had to let go mostly young workers. Instead, they let go all employees and rehired those they wanted to retain. The company paid a total of €270 million in various fees, a majority of which were settlement payments for dismissed employees.

Other areas that HR can help to shine a light on in the early stages of a deal include:

- Pension liabilities Many Western companies have defined benefit retirement plans, which promise employees a predefined pension on retirement. The risks of these plans not often found in Chinese companies can easily be underestimated. It is essential to ensure the company accurately discloses pension obligations and confirms assets are set aside to cover these obligations. Pension liabilities are often substantial and should be taken into pricing considerations.

- Total Rewards Western enterprises’ pay philosophy and salary structure can be very different from those of Chinese buyers. The Lenovo Group’s acquisition of IBM’s personal computer business is an example. Before the acquisition, the base salary of IBM employees was much higher than that of Lenovo employees. Re-levelling would be difficult, as a cut in salaries would have retention implications for IBM staff, and raising Lenovo staff salaries would incur enormous labor costs.

- Executive pay arrangements Western companies sometimes offer top executives a change-in-control severance agreement that compensates executives with a large amount of cash, stock, or related benefits when a company is acquired. For Chinese companies, such a benefit is rare. If these contracts are not thoroughly reviewed at the due-diligence stage, the buyer may have to pay a severance after the acquisition. For example, when Google acquired Motorola Mobility, ex-CEO Sanjay Jha received $66 million in compensation.

- Labor unions Labor unions play a different role in China than other parts of the world. In China, unions help organize workers and settle labor/ management disputes, rather than participate in decision making regarding corporate operations. This is very different from countries such as France, where a company with more than 50 employees must set up a labor union committee, and the union has the right to participate in making and vetoing labor rules. In many countries, the labor union has the power to stop an M&A on behalf of employees through a strike or other disruptive actions.

Involve HR in due diligence covering five risk areas:

- Compliance risk Identify whether the target company’s employment contract offering, terms and working conditions, union operations, and so on are in full compliance with social security, labor laws, and other related regulations.

- Financial risk Calculate the figures that may impact the purchase price, such as change in control indemnities, pension deficits or liabilities, cost of non-compliance, potential severance costs, immediate vesting of stock or long-term-incentive programs, and unsettled labor lawsuits.

- Culture risk Identify major cultural gaps that would make future collaboration or communication difficult, such as leadership dynamics, union-employee relations, and the level of mutual trust .

- Talent risk Identify critical roles, key talent, market competitiveness of executive compensation and general employee salaries, turnover rate, employee engagement levels, attitudes towards the deal, confidentiality agreements, and non-compete agreements. .

- HR operational risk Explore whether there are inconsistent HR systems, incomplete information or recordkeeping, poor vendor management, or lack of business-aligned HR policies or programs.

Challenge 2: Retaining key talent

Whatever the goal of a merger or acquisition — whether to tap into global markets or gain access to advanced technologies and management know-how — the success of the deal will largely depend on experienced leaders who understand, support, and guide the organization’s new vision. In most cases, the target company will have an existing culture and processes that need to be integrated into the acquiring entity.

One crucial challenge is how to retain the employees of the acquired company. Keeping some continuity in leadership can be the key to beginning normal operations as soon as possible.

Research has found that the earlier key talent is identified, the more likely retention will succeed (Figure 2).

It is troubling to note that Asian employers identify talent to retain later in the life cycle of a deal than do their global counterparts (Figure 3). Given the importance of key talent retention to the success of a deal, this could have the potential to put Asian employers at a significant disadvantage.

In March 2011, China-based Australia Dairy Corporation announced it would acquire stakes in Hyproca Dairy, marking the first M&A deal between a Chinese dairy company and a foreign milk powder enterprise. Learning that many employees at Hyproca Dairy intended to resign, Chen Yuanrong, CEO of Australia Dairy, promised not to change the management model, transfer Chinese employees over, or close the factory — the “three nos” approach. With the rollout of an incentive program to provide employees with stock options, the Chinese company successfully retained key employees, which helped to smooth over the often turbulent transitional M&A stage.

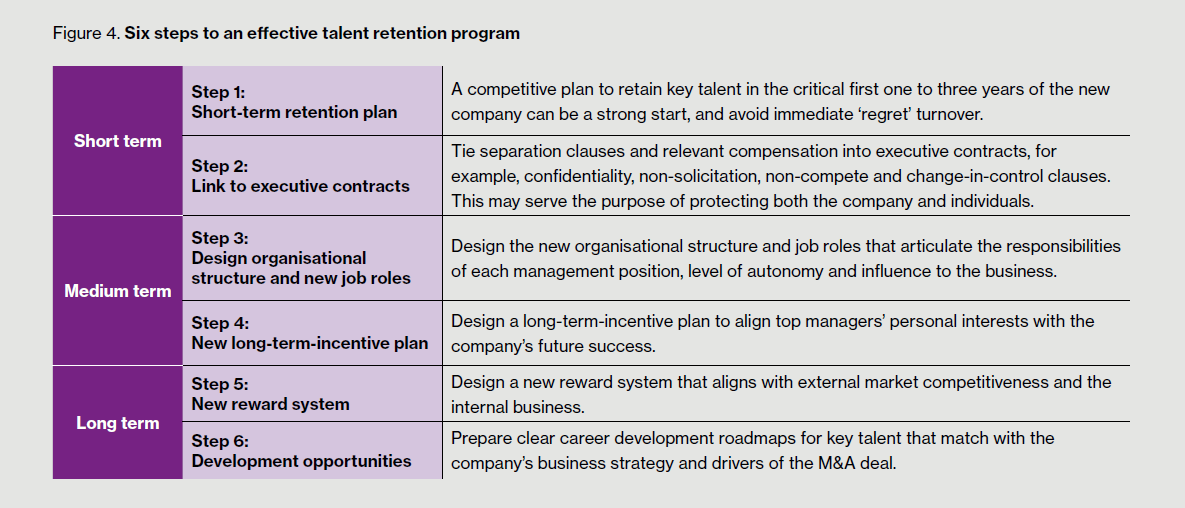

After key employees have been identified, the six-step process can retain talent.

It’s always important to understand what factors have been driving the deal. If the deal’s goal is to acquire advanced technology, then retaining R&D staff will be critical, and if acquiring the brand is the goal, then retaining marketing, customer services, and a sales force will be key.

Challenge 3: Differences in organizational and national cultures

Culture is a hot topic when it comes to Asian multinationals expanding globally. In China, cultural differences are strongly felt at the organizational level: Chinese leaders tend to manage companies through a comparatively rigid, top-down approach.

For example, when making decisions at the middle-management level, Chinese managers take into account senior management’s interests where Western managers tend to focus on financial results.Western companies base hiring decisions on individual performance and new job requirements, while Chinese companies also take the employee’s age and years of service into account.

In addition, Chinese employees’ relationships with their companies can be different than in the West. In China, employees tend to identify their relationship with the company from a moral perspective and are likely to develop a sense of commitment and loyalty toward the company. This is particularly noticeable in state-run enterprises.

Cultural gaps can be felt during acquisitions. A China automobile manufacturing group’s acquisition of a Swedish manufacturing company sparked worry among the Swedes who had strong national pride about the company and the brand. They were worried the alliance would diminish its brand image. The head of the engineers’ union at the Swedish company even cooperated with a local syndicate in Sweden to bid for the sale of the firm, although it eventually failed to raise enough funds to compete with the Chinese firm.

In order to be effective, cultural alignment should incorporate the following steps:

- Step 1 The top leadership team identifies the culture gap between the two companies and conceptualizes the desired new culture based on the merged company’s business goals. This would include culture as it relates to decision making, communication, degree of autonomy, and core values.

- Step 2 Leadership establishes a formal team to focus fulltime on culture integration tasks. This will facilitate desired behaviors and increase employee engagement and cohesiveness.

- Step 3 HR develops a “culture booklet” to promote role models and demonstrate real world examples that illustrate the new company’s core values to employees.

- Step 4 The company bolsters this with effective, ongoing communication and training programs.

- Step 5 The company aligns employee behavior with an appropriate reward system and performance management program.

Maintaining and strengthening employees’ engagement during change and uncertainty can be a long-term effort, but it can be very rewarding if it succeeds. Specific strategies will depend on the new organization’s goals and culture.

Challenge 4: Global mobility

The success of a merger or acquisition will depend largely on the expertise of leadership in guiding the new firm forward. While one part of this equation is to retain employees of the acquired company, Chinese organizations often have difficulties establishing a cadre of leaders with global expertise within their own ranks.

For example, when the Chinese electronic manufacturing company entered into a joint venture with a French firm in 2004, the company chairman launched a global recruitment drive to find an international assistant. However, this position could not be filled suitably, paving the way for the failure of the joint venture. In another example, when acquiring a Korean automotive manufacturer in 2005, the Chinese acquirer did not have any Korean-speaking personnel. Although the company retained the original management team from the Korean firm, a gap in cultural communication existed between the two sides.

For many Chinese companies, mobility difficulties generally fall into three areas:

- A lack of suitable expatriate talent Much of this stems a cultural issues expressed in an old Chinese saying: “No travelling far, while parents are still around.” Chinese employees, particularly the experienced, middle-aged, are usually reluctant to move overseas.

- Cultural integration Chinese employees tend to struggle with cultural integration, causing weaker performance when compared to that in the home country. This is compounded by inappropriate performance measures and compensation without incentives.

- Loss of talent Talent is easily lost after repatriation, because of a lack of suitable positions at home following an international assignment. With valuable overseas experiences, employees are easily poached by other globalizing companies.

Many multinationals have adopted some best practices to overcome the challenges of global Mobility; Danone, Rakuten, and Uniqlo made English a second official language. While difficult, but Chinese companies can move in this direction by asking top management to work in two languages. In doing so, they may avoid problems associated with ineffective communication during an overseas labor dispute or other conflict.

Other steps to consider to enhance in-house talent include:

- Develop a global recruitment process Some large multinational corporations such as Nissan and Sony develop their global businesses by recruiting non-Japanese executives.

- Create a plan to cultivate the organization’s talent pool Because of its global rotational training scheme, two-thirds of Komatsu’s executives have overseas experience.

It is also advisable to have a mobility mechanism that works through the cycle of an international assignment and includes the following aspects:

- Talent assessment and selection The filtering process should include a standardized test, 360-degree evaluation, and face-to-face interviews.

- A comprehensive talent incubation plan Such a plan would begin with self-diagnosis, and include training programs and personal mentorships.

- Business-oriented performance measurement The candidate’s assessment should be placed into the context of the business cycle (for example, start-up, mature, recession).

- A well-designed compensation and benefits program This should include statutory benefits, cost-of-living adjustments, relocation support, and health and wellness benefits.

- Repatriate management Understand the employee’s career intentions; help them adjust to a new life and new role; and make repatriate arrangements such as compensation and benefit program adjustments.

Challenge 5: Difficulties integrating core resources

One of the primary purposes of Chinese enterprises’ overseas M&A transactions is to obtain advanced technology and global brand management experience. To retain core personnel, Chinese enterprises often adopt the “three nos” policy: no change of management team, no Chinese expatriate onsite, and no factory shutdown.

Technological integration must be carried out through the close cooperation of acquirer and acquiree. If the buyer does not lend a hand in the management of the target firm, it will never attain the desired technological advantages. In the end, M&A transactions would merely provide the bought-out company with domestic markets and sales channels.

It is suggested that Chinese companies develop post-merger programs that match the current-state integration capability and degree of mutual trust. At the beginning of an acquisition to reassure the seller’s employees, a non-intervention management policy may be adopted. After a period of time, the Chinese buyer could arrange for business leaders and technical staff to interact through rotation, training, special project assignments, and site visits.

About the author: Willis Towers Watson (NASDAQ: WLTW) is a leading global advisory, broking and solutions company that helps clients around the world turn risk into a path for growth. With roots dating to 1828, Willis Towers Watson has 39,000 employees in more than 120 countries. We design and deliver solutions that manage risk, optimize benefits, cultivate talent, and expand the power of capital to protect and strengthen institutions and individuals. Our unique perspective allows us to see the critical intersections between talent, assets and ideas — the dynamic formula that drives business performance. Together, we unlock potential. Learn more at willistowerswatson.com.